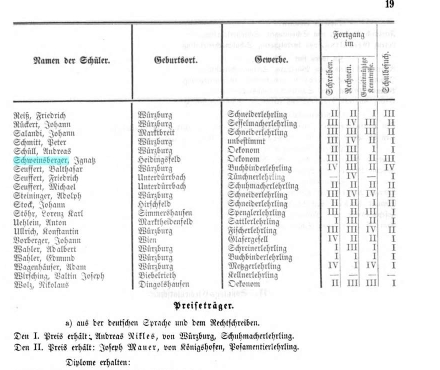

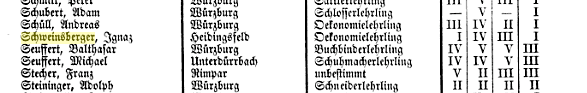

Ignaz [my grandmother Caroline’s grandfather] was born in 1844. We know nothing about Ignaz’ early life until he went to school. Below you can see the report cards for Ignaz for 1855-59 as reported in Jahres-Bericht des Polytechnischen Vereins zu Würzburg, the trade school that he attended. The columns are: name of scholar, birthplace, trade, reading/writing, arithmetic, general knowledge, continuous transition [i.e. passing grades… shown in the heading above the three just mentioned], and in the last far right column “failed visit” presumably meaning absence. “I” is the best grade and “V” is the worst. I haven’t copied the report cards for all of the hundreds of students, but rather copied enough of them to show how Ignaz was doing compared to other students. Grades below are for 1855-56 when Ignaz was about 11yrs; “Oekonom” in the third column from the left [trade] appears to be an archaic spelling of “economics;” presumably what we would now call “business” classes.  The four lines below the above table mention the students who received prizes for their work. Ignaz didn’t win any prizes. Below are his grades for the next year.

The four lines below the above table mention the students who received prizes for their work. Ignaz didn’t win any prizes. Below are his grades for the next year.  Below are grades for 1858-9 when Ignaz was serving as an “economics apprentice” [oekonomielehrling].

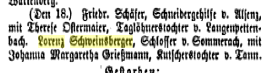

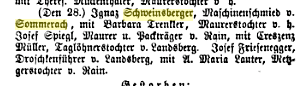

Below are grades for 1858-9 when Ignaz was serving as an “economics apprentice” [oekonomielehrling].  So by his last year Ignaz was a slightly better than average student with two grades of “I”. At age 24 Ignaz married Barbara Trenkler, age 23. Here is their wedding announcement from their local daily newspaper, the Munich Official Gazette [Münchener Amtsblatt] of 1868. Ignaz was a “maschinenschmied” or “machine smith” who was “v. Sommerach” or “of Sommerach,” and Barbara was listed as a “maurerstochter v. h.” or “mason’s daughter “of here,” i.e. from Munich.

So by his last year Ignaz was a slightly better than average student with two grades of “I”. At age 24 Ignaz married Barbara Trenkler, age 23. Here is their wedding announcement from their local daily newspaper, the Munich Official Gazette [Münchener Amtsblatt] of 1868. Ignaz was a “maschinenschmied” or “machine smith” who was “v. Sommerach” or “of Sommerach,” and Barbara was listed as a “maurerstochter v. h.” or “mason’s daughter “of here,” i.e. from Munich.  Barbara’s father, Johann, had died 29 December 1863 at age 59 yrs and her older brother Georg had died at age 21yrs in 1862. Unlike the Schweinsbergers, the Trenkler family of Munich was relatively large with many branches. Parts of the family had been prosperous enough to afford university education for their children. The result was that by the early to mid 19th Century, some Munich Trenklers were musicians/music directors, chemists, university professors, biologists, horticulturists, industrialists, physicians, and military officers. This educational advantage made the Trenklers one of the few branches of the family that really prospered before the last third of the 20th Century. I’ve collected 56 documents from the 19th Century about the Munich Trenklers, but only a few of Barbara’s close relatives can be identified with certainty. It is difficult to sort them out given so many possibilities.

Barbara’s father, Johann, had died 29 December 1863 at age 59 yrs and her older brother Georg had died at age 21yrs in 1862. Unlike the Schweinsbergers, the Trenkler family of Munich was relatively large with many branches. Parts of the family had been prosperous enough to afford university education for their children. The result was that by the early to mid 19th Century, some Munich Trenklers were musicians/music directors, chemists, university professors, biologists, horticulturists, industrialists, physicians, and military officers. This educational advantage made the Trenklers one of the few branches of the family that really prospered before the last third of the 20th Century. I’ve collected 56 documents from the 19th Century about the Munich Trenklers, but only a few of Barbara’s close relatives can be identified with certainty. It is difficult to sort them out given so many possibilities.

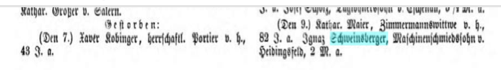

For Ignaz and Barbara life was not easy. They lost their first son a little more than a year after their marriage. The item in the news reads “Ignaz maschinenschmiedsohn” or “Ignaz, machine smith’s son;” he was listed as “gestorben” or “deceased” December 9 1869 at 2 month of age.  The notice lists the father’s home as Heidingsfeld, (one or the 13 named neighborhoods of Würzburg). Subsequently, Ignaz and Barbara had another son they named Ignaz. He died December 29 1872 at 9 days as recorded in the Münchener Amtsblatt: 1873. The son was listed as “Schlosserssohn” or “locksmith’s son.”

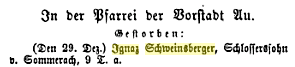

The notice lists the father’s home as Heidingsfeld, (one or the 13 named neighborhoods of Würzburg). Subsequently, Ignaz and Barbara had another son they named Ignaz. He died December 29 1872 at 9 days as recorded in the Münchener Amtsblatt: 1873. The son was listed as “Schlosserssohn” or “locksmith’s son.”  This notice shows the father as “from Sommerach.” Ignaz spent part of his early years in Heidingsfeld in south central Würzburg and part in Sommerach about 35km northeast of Würzburg/Heidingsfeld. Sommerach sat on the east side of the river Main. Sommerach was then, and still is, a very small village. The “v” or “von” was used just as we use the word “from” now to describe origin. Thus, I am “from St. Louis” or “from Oregon” depending on the context of the discussion. So Ignaz is sometimes listed as ”von Sommerach” or “von Heidinsfeld” or “von München” depending on whether he was describing where he was born or where he was currently living.

This notice shows the father as “from Sommerach.” Ignaz spent part of his early years in Heidingsfeld in south central Würzburg and part in Sommerach about 35km northeast of Würzburg/Heidingsfeld. Sommerach sat on the east side of the river Main. Sommerach was then, and still is, a very small village. The “v” or “von” was used just as we use the word “from” now to describe origin. Thus, I am “from St. Louis” or “from Oregon” depending on the context of the discussion. So Ignaz is sometimes listed as ”von Sommerach” or “von Heidinsfeld” or “von München” depending on whether he was describing where he was born or where he was currently living.

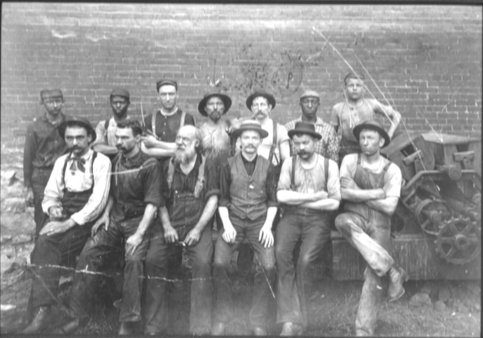

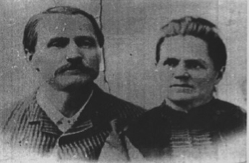

I don’t know whether they tried to name any more sons Ignaz. US Census forms indicate that eventually they had 14 children, 4 of whom survived to adulthood… about average for the pre-antibiotic/pre-immunization era. The dates of their marriage, as well as the death notices in the Munich Official Journal, indicate that Ignaz was already living in, or near, Munich by 1868, although the 1870 Adreßbuch für München still didn’t list them. Perhaps listing was a cost they couldn’t afford at that point. The only Schweinsberger listed in Munich in 1870 was Johann. This Johann Schweinsberger, a carpenter [tischler], is probably Ignaz’ uncle, but there is no strong documentation to support this interpretation. In Munich, Johann and Ignaz lived on opposite sides of the Isar River, about 2km apart. The Adreßbuch für München after 1872 listed Ignaz: “Schweinsberger Ignaz, Kleinmechaniker” living at 49 Falcon Street. A “little machinist” presumably means a metal worker who specialized in small metal mechanical devises, such as locks. I’m not sure when this picture was taken of them. I suspect it is long after they married. They look to be in their late 40s.  There is nothing in these records to suggest any obvious reason for going to America. However, family problems may have played a role. Next episode…Problems for the family patriarch – Johann Baptist Schweinsberger.

There is nothing in these records to suggest any obvious reason for going to America. However, family problems may have played a role. Next episode…Problems for the family patriarch – Johann Baptist Schweinsberger.